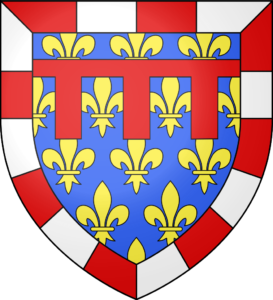

The royal House of Anjou is a cadet branch of the Capetian Royal House of France. It is one of three separate royal houses referred to as Angevin, meaning “from Anjou” in France. Founded by Charles I of Naples, a son of Louis VIII of France, the Capetian king first ruled the Kingdom of Sicily during the 13th century. Later the War of the Sicilian Vespers forced him out of the island of Sicily, leaving him with just the southern half of the Italian peninsula: the Kingdom of Naples. The house and its various branches would go on to influence much of the history of Southern and Central Europe during the Middle Ages.

History

Charles of Anjou was the posthumous son of king Louis VIII of France. His brother Louis IX who succeeded to the French throne in 1226 gave him the titles of Count of Anjou and Maine. The feudal County of Anjou was a western vassal state of France which the Capetians had wrested from the English only a few decades earlier. He married the heiress of the County of Provence, Beatrice of Provence who was a member of the House of Barcelona. After fighting in the Seventh Crusade, His Holiness Pope Clement IV, offered him the Kingdom of Sicily, which included not only the island of Sicily but also the southern half of the Italian peninsula. The reason behind this offer was a conflict between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire which was ruled by the House of Hohenstaufen.

It was at the Battle of Benevento that Charles gained the Kingdom of Sicily after he beat the Hohenstaufens and this was cemented after victory at Tagliacozzo. He signed the Treaty of Viterbo in 1267, an alliance with the exiled Baldwin II of Constantinople and William II of Achaea.

Taking advantage of the precarious situation of the remains of the Empire in the face of rising Greek power, he obtained confirmation of his possession of Corfu, the suzerain rights over Achaea, and sovereignty over most of the Aegean islands. Furthermore, the heirs of both the Latin princes were to marry children of Charles, and Charles was to have the reversion of the Empire and principality should the couples have no heirs. With few options to check the Byzantine tide, he was well placed to dictate terms.

The treaty also gave him the possession of cities in the Balkans, the main one being Durazzo, Charles had fully solidified his rule over Durazzo by 1272, creating a small Kingdom of Albania for himself.

Charles’ wife Beatrice died on 23 September 1267, and he immediately sought a new marriage to Margaret, Countess of Tonnere, the daughter of Eudes of Burgundy.

Albania

Charles new kingdom extended from the region of Durrës (Durazzo, then known as Dyrrhachium) south along the coast to Butrint. A major attempt to advance further in direction of Constantinople, failed at the Siege of Berat ( 1280-1281). A Byzantine counteroffensive soon ensued, which drove Charles out of the interior by 1281. The Sicilian Vespers further weakened his position, and the Kingdom was soon reduced by the Epirotes to a small area around Durrës. The Angevins held out here, however, until 1368 when Stephen of Durazzo lost the city to Karl Thopia. In 1392, Karl Thopia’s son returned Durazzo and his domains to the Republic of Venice thus ending the rule of the House of Anjou in Albania.

Sicily 1266–1282

Charles administration of Sicily was generally fair and honest but it was also stringent despite this unrest simmered in Sicily because its nobles had no share in the government of their own island and were not compensated by lucrative posts abroad, as were Charles’s French, Provençal and Neapolitan subjects; also Charles spent the heavy taxes he imposed on wars outside Sicily, making Sicily somewhat of a donor economy to Charles’ nascent empire.

The unrest was also fomented by Byzantine agents to thwart Charles’s projected invasion of Constantinople, and by King Peter III, who saw his wife Constance as rightful heir to the Sicilian throne. On the 3oth March, 1282 during the sunset prayer marking the beginning of the night vigil on Easter Monday at the Church of the Holy Spirit just outside Palermo, the uprising took place and was to be known as the Sicilian Vespers. Beginning on that night, thousands of Sicily’s French inhabitants were massacred within six weeks. Peter III of Aragon supported the rebels and joined the war that was to last until 4th September 1282, when Peter was crowned as King Peter I of Sicily though he ruled only over the island as Charles kept the southern part of the Italian peninsula that was to be known as the Kingdom of Naples.

Charles planned an invasion of Sicily but his health was failing him and the plan thwarted. He died in Foggia on the 7th January 1285.

Kingdom of Naples

After the death of Charles I, his son Charles II succeeded him on the Neapolitan throne and he in turn was succeeded by his son Robert on the 5th May 1309. Robert, the Wise, as he was known died on the 20th January 1343 and was succeeded by his grand daughter Joanna I, until her murder in May 1382. She was succeeded on the throne by her second cousin and son of Louis of Durazzo, Charles III who reigned until his death in 1836. The throne passed to his son, Ladislau, who reigned until his death on 6th August 1414.

Queen Joanna II was born on 25 June 1373, as the daughter of Charles III of Naples and Margaret of Durazzo. In 1414, she succeeded her brother Ladislaus and at that date she was 41 years old and was already the widow of William, Duke of Austria. She married twice, but had no children and had adopted Louis III of Anjou in 1431 but he died in 1434 and she offered his younger brother René to inherit her kingdom in his place. In 1438 he set sail for Naples, which had been held for him by his wife, the Duchess Isabel.

The revival of the defunct Royal House of Anjou-Naples by King Alfonso XIII of Spain

Basil d’Anjou-Durassow-Schiskow, who King Alfonso XIII of Spain proclaimed head of the defunct Neapolitan House of Anjou-Naples and recognized as Duke of Durazzo in 1911.

The story of the revival of the Royal House of Anjou-Naples is fascinating to say the least and it was the result of an act of revenge of the Spanish king against members of his family whose pretensions to the thrones of France and the Two-Sicilies, he considered were out of line.

To understand the full story we must go to the beginning of the family saga. The story starts with H.R.H Infante Don Enrique de Borbon, 1st Duke of Seville who was grandson and great-grandson of kings of Spain and brother in law to Queen Isabella II of Spain. His uncle, King Fernando VII of Spain had bestowed on him the title of Duke of Seville.

In 1833, his uncle the king died and the Court was divided between the supporters of the the new queen, Isabel II of their uncle, Infante Carlos Maria Isidro de Borbon , who founded what was to be known as the Carlist line. This dynastic affair paved the way to the Carlist wars in Spain. The maternal aunt of Don Enrique, queen Maria Cristina (she was sister of Don Enrique’s mother Infanta Luisa Carlota), widow of Fernando VII, was appointed regent for her young daughter.

The second marriage of the queen regent with Agustín Fernando Muñoz and Sánchez in 1833 caused disagreements between her and her sister, the infanta Luisa Carlota, a fact that ended up by banishing Luisa Carlota and her family to Paris, where the aunt of both, Queen Maria Amalia, wife of Luis Felipe I of France.

Enrique and his brothers were educated in the French capital, and at the Lyceum Henri IV, he met his cousin, Antonio de Orleans. Already at that time there arose an intense rivalry between the two that would end, as will be seen, tragically years later. Don Enrique spent a season in Belgium, where his aunt, the wife of Leopoldo I of the Belgians, reigned. There they learned in 1840 that Queen Isabel II’s government had sent her mother the Queen Regent and her husband to exile.

Finally Don Enrique could return to Spain, and soon began his military career in Ferrol, where he was praised for his excellent conduct. In 1843 he was promoted to lieutenant of a frigate and was commander of the brig Manzanares. In 1845 he was already frigate captain, but that year would mark him for reasons beyond the naval militia.

At that time the possibility was discussed of marrying Don Enrique to the queen. Nevertheless, she ended up marrying his homosexual and effeminate brother, Infante Francisco de Asis, Duke of Cadiz. The queen’s younger sister, Luisa Fernanda married Antonio of Orleans, Duke of Montpensier.

Offended by what he considered a grievance, and accused of having participated in a revolt against the monarchy in Galicia, the Infante was expelled from Spain in March 1846, shortly before the wedding of his brother and the queen, nuptials to which he did not attend. Don Enrique took refuge in Belgium, where his sister Isabel Fernandina was. At that time his name was shuffled as a possible candidate for the throne of Mexico, a matter in which don Enrique did not seem to be too interested.

Shortly afterwards, in order to negotiate the Mexican affair, the Infante was able to return to Spain, where he met Elena María de Castellví and Shelly (Valencia, October 16, 1821 – Madrid, December 29, 1863), daughter of Antonio de Padua de Castellví and Fernandez de Cordoba, XII Count of Villanueva, X Count of Castellá and VIII Count of Carlet, and Margarita Shelly of MacCarthy, sister of Edmundo Shelly and MacCarthy, Colonel of Infantry and Secretary of King Ferdinand VII . Soon an idyll arose between them, but the queen’s opposition was assured. The marriage, celebrated secretly in Rome, Pontifical States, 6 of May of 1847, did not enjoy in principle of the approval of Queen Isabel II. Once they returned to Spain the couple was expelled to Bayonne, and later settled in Toulouse.

From France, Don Enrique proclaimed himself several times revolutionary, and even asked to join the First International.Immediately he was stripped of his titles, and ceased to be considered an Infante of Spain. Meanwhile, his children were born without rank or title, and in 1849 he asked for the Queen’s pardon so that he could return to Spain. The family settled down in Valladolid in 1851, but soon they were forced to return to France. Later, in 1854 they were able to return to Spain, and they moved to Valencia, where their fourth child was born and where the second died, Luis. Don Enrique recovered his ducal title, but not that of Infante of Spain.

Soon after, the Duke of Seville returned to manifest his leftist ideas, and was again expelled to France. He was able to return in 1860, and ascended to the rank of general captain of the navy, and three years later was promoted to lieutenant-general. That year of 1863 his wife died giving birth to his fifth daughter, and was buried in the madrileño convent of Descalzas Reales, and not in San Lorenzo de El Escorial as she was not an Infanta of Spain.

Between November of 1864 and January of 1865, he was exiled to Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands, where contravening the orders of the authorities of Madrid was received with honours by the local authorities in their different visits to localities of the island as a member of the royal household. The 29th of January of 1865 he returned to the peninsula.

Don Enrique tried, in vain, to remarry a European princess, and soon began to attack the government of his sister-in-law and cousin, Queen Isabel II. His actions led to the deprivation of his titles and honours, and was again exiled in 1867.

Forgetting their close kinship with Isabel II, Don Antonio de Orleans supported with his great fortune the overthrow of the queen by the ultra liberal elements of the army. After the success of the revolution of 1868, the Queen and Don Enrique met in the Parisian exile, where the dispossessed Duke of Seville tried to persuade her cousin to abdicate in favour of her son, Prince Alfonso as a compromise solution to preserve the throne for the Bourbon dynasty. At that time the Queen refused and after several letters of supplication to the revolutionary government, he was able to return to Spain. Back in Madrid, he soon tried to be considered for the vacant throne, for which his greatest rival was his childhood enemy, Don Antonio de Orleans, Duke of Montpensier, married to the exiled queen’s sister, Infanta Luisa Fernanda.

However, the revolutionaries had already pronounced that the Bourbons would never again reign in Spain as they were accused of all the national ills. The revolutionary government had decided to invite to the Spanish throne a foreign dynasty. The Duke of Seville’s dream to lead a progressive monarchy had collapsed so Don Enrique’s main worry was the education of the future king, Prince Alfonso and his immediate situation. He tried in vain to persuade the Queen to educate the Prince of Asturias in England in liberal and parliamentary principles, far away from the European conservative courts.

In 1869, he published a violently anti-montpensier pamphlet, in which he describes his opponent in his true colours. In a letter of March of 1870, Don Enrique openly insulted the one who had been his enemy since childhood. As was custom in those days, Montpensier reacted by challenging the Duke of Seville to a gun duel that took place on the 12th of March in the Dehesa de los Carabancheles. Don Enrique returned to Spain ready to confront the odious prince of Orléans, who had contributed so much to the overthrow of the Bourbon monarchy and with whom he had old personal accounts that dragged from as far as the times of the lycee in Paris! The Duke of Seville was killed that day.

Montpensier was sentenced to one month in exile and the payment to the family of Don Enrique of 30,000 pesetas, which the Duke’s sons refused to accept. He was buried in the cemetery of San Isidro de Madrid, since El Escorial, which would have corresponded for an Infante of Spain, was forbidden, after a massive masonic funeral. His children were left , in the exile of Paris, orphans and without resources, in the care of their uncle, the effeminate king consort, Don Francisco de Asis.

A distant uncle of the Bourbon-Seville, the last Duke of Parma, Robert of Bourbon, therefore, brother of Dona Margarita de Borbón-Parma (the queen of the Carlists), who took pity on the unfortunate fate of Don Enrique’s children, invited them to live with him in Nice. Through the beneficent influence of this prince, Don Carlos VII (king of Spain for the Carlists) showed interest in their fate and he invited them to join his army as cousins and princes of the House of Bourbon.

On the 16th of July of 1873, Don Carlos (VII) entered Spain followed by his army and accompanied by the young Don Enrique de Borbon y Castellvi and his brothers Don Alberto and Don Francisco de Paula. The fact is that they fought in the fronts of Catalonia, Valencia and Aragon. All three brothers served in the Carlist army against the foreign king Amadeo of Savoy that had been invited by General Prim to be king of the revolution and after his overthrow, the First Republic. They received decorations for their bravery.

After the restoration of the monarchy with Alfonso de Borbon on the throne as King Alfonso XII, they asked Don Carlos (VII) to release them from their oath of allegiance to his person as they did not want to fight against their cousin, the new king and they returned to France. From there, they enrolled to serve King Alfonso XII on the island of Cuba, in the war against the independence insurgents.

Don Enrique, by then the II Duke of Seville, accepted the presidency of the Heraldic Council of France and walked his noble figure at the European Courts where he was always received as the prince of Bourbon he was. In 1870, he married Josefina de Paradé and Sibie, who gave him three daughters. After the premature death of King Alfonso XII, he was the victim of a cruel political persecution by the Queen Regent, Maria Cristina of Habsburg, who did not forgive him for criticizing her. He died in 1894 on the high seas, when he returned from the Philippine Islands, where he had held the position of Governor of Tabayas.

In 1889, Don Enrique signed a document by which he reserved his rights to the succession of the crowns of Spain and Two-Sicilies, which constitute in itself a whole manifest against the injustice of their situation. It read:

“I, Enrique Pio de Borbón, II Duke of Seville, head of the branch founded by the Infante de España, Don Enrique Maria Fernando de Borbón, Duke of Seville, my father; I solemnly declare before God and of men, to reserve in the most formal and absolute way all eventual rights to the crowns of Spain and of the Two-Sicilies. That I, my descendants, my brothers, their descendants and my sister, we have both from the point of view of the pragmatics of male succession as from the female. I declare to keep them forever, full and complete, for whatever may happen. In faith I sign it: Enrique Pío de Borbón, II Duke of Seville.

Maisons-Laffite, France, on April 24, 1889.

This very significant document shows, again, despite all the disagreements with the Royal Family, that the children of the Infante Don Enrique were aware of their rights and duties as Members of the House of Bourbon. So much, so that at the death of the II Duke, in 1894, his brother Don Francisco remained as head of his family and as such he proclaimed himself Duke of Anjou, that is: Head of the entire Capetian House.

The gesture, so typical of an impulsive man provoked severe reproaches of very different sectors. Many historians consider it childish or anecdotal. It is not in any way. Don Francisco de Borbon y Castelvi, knew well the laws of primogeniture that govern the succession of the throne of France, and he was aware that his rights came solely from the indolent attitude of Carlos (VII) of Bourbon, the head of the Carlist branch whom he had served, in regard to the Headship of the Capetian House.